“Now I do not have flowers blooming in my life. When I marry, one flower will bloom; when I see my children grow, another one will bloom.”

This was one of the last things Behzad told me when we met, as if to impress upon me just why he had come all the way to Europe from Afghanistan. Of course, he didn’t leave his beloved homeland to find a wife. Behzad left Afghanistan because he was personally threatened by daily violence that made it impossible for him to make the most of his considerable potential.

Like other people who come in their multitudes to seek asylum in Europe, Behzad was searching for peace. He repeated this over and again: “I have no wishes, just to live peacefully. Any peaceful area is OK for us, it is not important whether it is Austria, Sweden, France, just peace, very important. We don’t know about our life, what will happen. But we must live in peace and calm and get our goals.”

Behzad found a peaceful space in Austria, in an Asylwerberhaus (centre for asylum seekers) in Herzogenburg, a town about an hour away from Vienna. This is where I met him, in March 2016, when I went on a mission for the Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) to meet refugees who had come to Europe via the so-called Balkan route, from Turkey to Greece and onwards – a route that has since been closed.

Apart from sharing his own story, Behzad was my guide and translator that day in Herzogenburg. His hospitality was marked by generosity, respect and joy. He showed me around the centre and introduced me to fellow residents. He brewed delicious tea with spices, insisted I eat oranges, and fretted that I was working too hard. Throughout the afternoon, Behzad kept slipping his own thoughts in-between my interviews with the other asylum seekers, usually prompted by the stories of fellow Afghans. Like, “If God wants something, we can’t change it.”

Some of Behzad’s words have a mournfully prophetic ring to them now. Less than four months after we met, on 14 July, Behzad died in hospital in Austria, a week after a horribly tragic accident in a lake. The accident happened on his 28th birthday when he went swimming with friends. Somehow he got into difficulties while swimming and went under. His frantic friends, who could not swim, said he was rescued in under half a minute. But it was too late.

I was deeply sad when I heard about Behzad’s premature death. Our sole encounter had left a strong impression on me and the tragic news prompted me to wonder why this was so. I think it was because Behzad was so keenly alive. He wanted so much to live life to the full.

Most of the the refugees I have interviewed, throughout years of working for JRS, are eager to tell me about the trials they have left behind and what they hope to find in the country where they seek refuge. They need to tell their story.

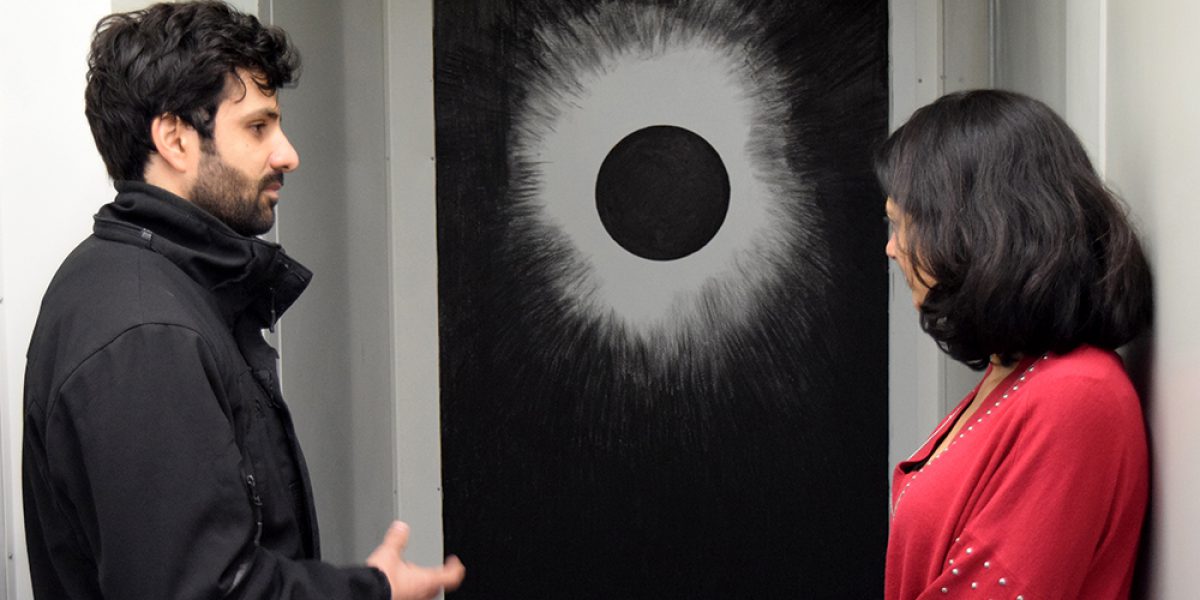

No exception, Behzad had a very creative way of telling his – like the metaphor of the flowers. He read meaning into lots of things. His surname, Ghraub, means “sunset” – this was the first thing he told me. Walls of the Asylwerberhaus were plastered with his paintings, each of which had a meaning. I wish I had listened more intently to the detailed explanations.

In other words, Behzad truly managed to convey the longing he had for life and the compelling reasons why he could not live any longer in Afghanistan. A smart and accomplished young man, he had plenty going for him back home. He was a graduate in biology and business administration and had several years of work experience under his belt, including jobs with two foreign NGOs – his English was excellent – and dean of economics at a private university.

Behzad’s beginnings were humble: he started out as a tailor in Taliban times but worked his way up rapidly once he got the opportunity. “I tried to improve my talent.” His enthusiasm for life went beyond work and study. Behzad told me he was on the national table-tennis team, and of course he had his painting.

Behzad’s success would turn out to be the reason for his downfall. Like countless educated Afghans, Behzad came under threat simply because he worked for foreign organizations (viewed by some extremists as betrayal), because he earned money that begged to be stolen, and because he had the identification to prove it. Travelling along lawless roads from one place to another in Afghanistan proved to be way too risky.

“I could not meet my family for six months because there were different problems on the road. They stop you, they take your mobile phones, your money. They ask, why do you have an ID card? Why do you work with NGOs? Having an ID is dangerous because it is obvious you work for a foreign organization – the cards state where you work.”

Behzad did his best to steer clear of trouble. His first brush with violent reactions to his chosen employment happened in Kata Kala, a small village in his province of Faryab.

“I was working as a pharmacy officer and we used to go to Kata Kala every Saturday and return to the city every Thursday,” he recalled. “One day, a lot of armed men came to our clinic, tied us with wires and beat us with guns. We had to resign and I found a new job in the city as a marketing officer. I put as much distance as possible between myself and them.”

Who is “them”? Blaming the Taliban was too facile an answer, insisted Behzad. In a massive country with swathes of territory outside government control, hundreds of illegal militia groups loyal to local warlords operate unhindered and prey on hapless civilians.

Eventually, Behzad managed to get a plum job at a private university in Mazar-i-Sharif, Afghanistan’s third largest city, where he worked for nearly three years as dean of the economic faculty. Soon he found himself facing violence again: “When someone is a teacher, they target.”

Apart from facing the constant danger of robbery, “one day, someone stopped my car and tried to shoot me,” Behzad faced another threat from a somewhat surprising source: “When some students failed their exams, they threatened to kill me more than once.”

Greatly troubled, Behzad finally came to the decision – supported by his parents – that his life in Afghanistan, hard as he had worked for success, was untenable: “I had everything, a car, a house, more than 30 teachers under my direction, but life is life.”

Hearing that “people were going to Europe” sealed his fate. Behzad joined the flow and arrived at the end of 2015, ending up in Herzogenburg. Here Behzad said he was grateful for the facilities and friendship he found, and always eager to lend a helping hand to fellow asylum seekers who were not as articulate and confident as he was.

He said: “I am happy I am here with kind people. And I try to help the others while I am here. For example, I accompany them to the hospital. This is my wish. I try to keep busy all the time, to help, to draw…”

Behzad made it clear that although he wanted to be in a peaceful and safe place, he would return to Afghanistan “when I feel there is no problem, because homeland is homeland.”

Behzad returned to his homeland to be buried. As he lay unconscious in hospital, his cell phone rang again and again in his friends’ hands: his family were trying to contact him. Eventually his brother was informed. Margarete Erber, the owner of the premises of the Asylwerberhaus, said: “For his friends it was clear that his body must go back to Afghanistan. A friend of the family who has been living in Vienna for a long time organized the transport of the corpse.”

Behzad came to Europe to find life and found death instead. The flowers he dreamed about, will never bloom now. This is an unspeakably terrible tragedy. But at least he did leave flowers blooming in the lives of others, both in Afghanistan, where he achieved so much against high odds, and in Herzogenburg, where he won the hearts of fellow asylum seekers and Austrians in a short time.

The day after Behzad’s funeral in Afghanistan, a memorial service was held at the Mosque of Herzogenburg, where asylum seekers from the centre used to go to pray. More than 100 people attended. Margarete said: “We grew together as a community in pain and hope. After the service, we all ate together in the yard of the mosque. We talked, remembered… And tears, again and again tears. Behzad was a person of integration and in his death he brought us all together once again even more intensively.”

– Danielle Vella, JRS Europe